This policy uses some strategies first developed by Motorcycling Australia.

Background

For trips where public transport, walking and cycling are not good options people should consider using a two-wheeled motor vehicle (TWMV) rather than a car.

Switching from a car to a motorcycle, scooter or electric bike is an easy way for people to reduce congestion, greenhouse emissions and save money on fuel.

TWMVs make more efficient use of fuel, road space and parking space than a single occupant car and can play a part in the campaign to reduce congestion and climate change.

Statistics on fuel efficiency are available here

When driven below the speed limit TWMVs also pose less of a safety risk to other road users than cars, trucks and buses due to their weight.

TWMVs are a more affordable transport option than driving a single occupant car, and will also help preserve oil reserves for essential agricultural, medical and transport uses.

All levels of Government should be doing more to encourage people to switch from their car to TWMVs.

Proposed strategies

More free parking spaces for TWMVs at activity centres and public transport nodes. Parking must be safe, conveniently located and ensure pedestrian, wheelchair and cyclist access is not obstructed. Car parks should be reclaimed for TWMV parking where possible.

Inclusion of two-wheeled motor vehicles in National Road Transport policies

Reduction in registration fees for TWMVs

Provision of TWMV-only lanes on key arterial roads

Exemption from tolls on tolled roads and infrastructure for TWMVs

Mandatory TWMV parking to be included in the construction plans for new buildings

Integration of TWMVs into the planning for Public Transport projects, such as park and ride for bikes.

A national standard that restricts the speed of new TWMVs available for the general public to 120km/hr

Advertising campaigns to encourage people to switch from a car to a two-wheeled motor vehicle

Government purchase of electric bicycles for use by employees and citizens

Fuel efficiency, in its basic sense, is the same as thermal efficiency, meaning the efficiency of a process that converts chemical potential energy contained in a carrier fuel into kinetic energy or work. Overall fuel efficiency may vary per device, which in turn may vary per application, and this spectrum of variance is often illustrated as a continuous energy profile. Non-transportation applications, such as industry, benefit from increased fuel efficiency, especially fossil fuel power plants or industries dealing with combustion, such as ammonia production during the Haber process. The United States Department of Energy and the EPA maintain a Web site with fuel economy information, including testing results and frequently asked questions.

In the context of transportation, "fuel efficiency" more commonly refers to the energy efficiency of a particular vehicle model, where its total output (range, or "mileage" [U.S.]) is given as a ratio of range units per a unit amount of input fuel (gasoline, diesel, etc.). This ratio is given in common measures such as "liters per 100 kilometers" (L/100 km) (common in Europe and Canada or "miles per gallon" (mpg) (prevalent in the USA, UK, and often in Canada, using their respective gallon measurements) or "kilometres per litre"(kmpl) (prevalent in Asian countries such as India and Japan). Though the typical output measure is vehicle range, for certain applications output can also be measured in terms of weight per range units (freight) or individual passenger-range (vehicle range / passenger capacity).

This ratio is based on a car's total properties, including its engine properties, its body drag, weight, and rolling resistance, and as such may vary substantially from the profile of the engine alone. While the thermal efficiency of petroleum engines has improved in recent decades, this does not necessarily translate into fuel economy of cars, as people in developed countries tend to buy bigger and heavier cars (i.e. SUVs will get less range per unit fuel than an economy car).

Hybrid vehicle designs use smaller combustion engines as electric generators to produce greater range per unit fuel than directly powering the wheels with an engine would, and (proportionally) less fuel emissions (CO2 grams) than a conventional (combustion engine) vehicle of similar size and capacity. Energy otherwise wasted in stopping is converted to electricity and stored in batteries which are then used to drive the small electric motors. Torque from these motors is very quickly supplied complementing power from the combustion engine. Fixed cylinder sizes can thus be designed more efficiently.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Energy-efficiency terminology

"Energy efficiency" is similar to fuel efficiency but the input is usually in units of energy such as British thermal units (BTU), megajoules (MJ), gigajoules (GJ), kilocalories (kcal), or kilowatt-hours (kW·h). The inverse of "energy efficiency" is "energy intensity", or the amount of input energy required for a unit of output such as MJ/passenger-km (of passenger transport), BTU/ton-mile (of freight transport, for long/short/metric tons), GJ/t (for steel production), BTU/(kW·h) (for electricity generation), or litres/100 km (of vehicle travel). This last term "litres per 100 km" is also a measure of "fuel economy" where the input is measured by the amount of fuel and the output is measured by the distance travelled. For example: Fuel economy in automobiles.

Given a heat value of a fuel, it would be trivial to convert from fuel units (such as litres of gasoline) to energy units (such as MJ) and conversely. But there are two problems with comparisons made using energy units:

- There are two different heat values for any hydrogen-containing fuel which can differ by several percent (see below). Which one do we use for converting fuel to energy?

- When comparing transportation energy costs, it must be remembered that a kilowatt hour of electric energy may require an amount of fuel with heating value of 2 or 3 kilowatt hours to produce it.

[edit] Energy content of fuel

The specific energy content of a fuel is the heat energy obtained when a certain quantity is burned (such as a gallon, litre, kilogram). It is sometimes called the "heat of combustion". There exists two different values of specific heat energy for the same batch of fuel. One is the high (or gross) heat of combustion and the other is the low (or net) heat of combustion. The high value is obtained when, after the combustion, the water in the "exhaust" is in liquid form. For the low value, the "exhaust" has all the water in vapor form (steam). Since water vapor gives up heat energy when it changes from vapor to liquid, the high value is larger since it includes the latent heat of vaporization of water. The difference between the high and low values is significant, about 8 or 9%.

In

thermodynamics, the thermal efficiency ( )

is a

dimensionless performance measure of a thermal device such as an

internal combustion engine, a

boiler,

or a

furnace, for example. The input,

)

is a

dimensionless performance measure of a thermal device such as an

internal combustion engine, a

boiler,

or a

furnace, for example. The input,

,

to the device is

heat, or

the heat-content of a fuel that is consumed. The desired output is

mechanical

work,

,

to the device is

heat, or

the heat-content of a fuel that is consumed. The desired output is

mechanical

work,

,

or heat,

,

or heat,

,

or possibly both. Because the input heat normally has a real financial

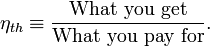

cost, a memorable, generic definition of thermal efficiency is[1]

,

or possibly both. Because the input heat normally has a real financial

cost, a memorable, generic definition of thermal efficiency is[1]

From the

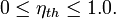

first law of thermodynamics, the output can't exceed what is input,

so

When expressed as a percentage, the thermal efficiency must be between 0% and 100%. Due to inefficiencies such as friction, heat loss, and other factors, thermal efficiencies are typically much less than 100%. For example, a typical gasoline automobile engine operates at around 25% thermal efficiency, and a large coal-fueled electrical generating plant peaks at about 46%. The largest diesel engine in the world peaks at 51.7%. In a combined cycle plant, thermal efficiencies are approaching 60%.[2]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Heat engines

When transforming

thermal energy into

mechanical energy, the thermal efficiency of a

heat engine is the percentage of heat energy that is transformed

into

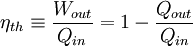

work. Thermal efficiency is defined as

[edit] Carnot efficiency

The

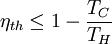

second law of thermodynamics puts a fundamental limit on the thermal

efficiency of heat engines. Surprisingly[citation

needed], even an ideal, frictionless engine can't

convert anywhere near 100% of its input heat into work. The limiting

factors are the temperature at which the heat enters the engine,

,

and the temperature of the environment into which the engine exhausts

its waste heat,

,

and the temperature of the environment into which the engine exhausts

its waste heat, ,

measured in the absolute

Kelvin

or

Rankine scale. From

Carnot's theorem, for any engine working between these two

temperatures:

,

measured in the absolute

Kelvin

or

Rankine scale. From

Carnot's theorem, for any engine working between these two

temperatures:

This limiting value is called the Carnot cycle efficiency because it is the efficiency of an unattainable, ideal, lossless (reversible) engine cycle called the Carnot cycle. No heat engine, regardless of its construction, can exceed this efficiency.

Examples of

are the temperature of hot steam entering the turbine of a steam power

plant, or the temperature at which the fuel burns in an internal

combustion engine.

are the temperature of hot steam entering the turbine of a steam power

plant, or the temperature at which the fuel burns in an internal

combustion engine.